Why Do Silos Suck

Voted "Best Looking Corporate Silo" 2022

When you hear the term “silo” used to describe business structures, it is nearly always a pejorative, a “four letter word” in the truest sense. Development teams that subscribe to Agile practices often lament how “silo-ization” slows down ongoing work. You can expect more colorful language when a decision seems to work directly against the goals of a project, halting work or adding tasks that seem to add no real value.

Yet despite all the bellow and bluster, silos continue to remain a concrete reality in most companies. And why wouldn’t they? After all, the silo typically reflects the org chart structure, which logically breaks up teams across unique disciplines and responsibilities, such as development, IT, and security.

So silos aren’t going anywhere, yet they cause so much trouble. What to do?

That’s a BIG question, with a multifaceted answer.

We start unraveling this knot by looking deeper at the root problems triggered by silo’d org structures. I won’t bury the lead: silos are a crutch that obscure or even facilitate bad behaviors. If we can better identify and understand the bad behavior, silos become less of a concern.

We need a thing!

It always starts with The Ask: someone, somewhere needs a change to occur in The Product(tm) that is your company’s technology status quo. The request can be almost anything: new product feature, a bug fix, infrastructure change, data export, you name it. It can affect internal or external systems; both are critical to your business’ success, so it doesn’t matter.

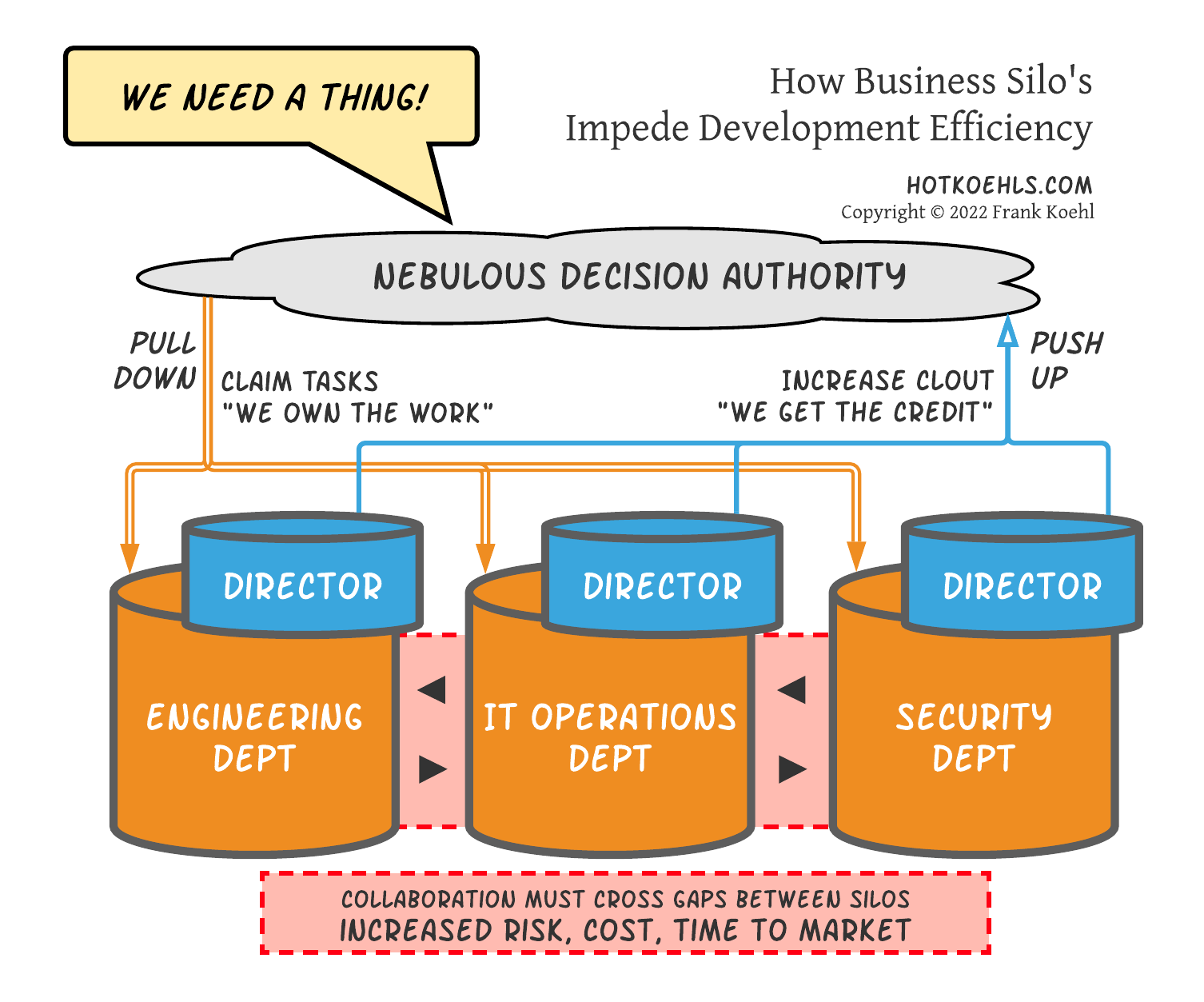

In software projects, accomplishing The Ask typically requires a coordinated effort across at least 3 Key Verticals.

- Development - build

The Product - IT Operations - run

The Product - Security - make sure

The Productis adequately defended

The lines between these groups is often blurry and varies between companies. Your product, industry, or org structure may use different labels, combine roles, or include more groups. This is a common and reasonable breakdown, so we’ll use it for illustration purposes.

Complicating matters is the dichotomy of Product Authority (business direction) and Subject Authority (technology implementation). These opposing forces create a tension in making decisions: who gets final say, and when?

Subject Authority:

I understand the technical intricacies. It’s gotta work right!

Product Authority:

I understand what’s best for the business, and what customers want. It’s gotta address the market needs!

The real problem is that these dueling dimensions of Product and Subject Authority compound with the Key Verticals. Each vertical and individual is naturally biased towards itself — we are human, fallible and self-interested — which is just as likely to get things moving as it is to gum up the works.

In other words, you don’t simply have “Product vs Subject” tension, but also “Development vs IT vs Security.” It’s a multi-dimensional mess, no wonder decision making is nebulous and impossible to predict.

With me so far? Maybe? No? Let’s add some pictures!

These influences, biases, and authorities all coalesce into what I call the Nebulous Decision Authority (NDA), aptly described and represented as an amorphous blob. On any given decision, the NDA will include anyone with influence, official or unofficial. The collection of decision makers actually changes for each decision. The relative weight of each decision maker also shifts; security folks will have a louder voice if the problem has a strong security component, for example.

Each NDA members’ communication skills, technical skills, and responsibilities within your organization’s hierarchy will further alter the landscape. The shift in decision power can be subtle or dramatic.

Politically charged environments further exacerbate self-interest and bias. In my experience, overt political maneuvering has a universal net-negative effect on the work. An individual or department may “win,” but some downstream recipient — such as team members, customers, or product quality — always suffers a setback.

In short, the NDA is a human-driven chaos machine, and shouldn’t be trusted to make consistent decisions.

The Ask ultimately gets championed by someone in the NDA group, even if it originated externally, so there’s strong potential for bias toward individual interest and agendas. This bias drives the Verticals to act as individually minded elements, rather than parts of a whole. That friction slows down — or in some cases entirely disrupts — collaboration between individual contributors from separate Verticals.

- All technical problems are business problems.

- All business problems are people problems.

This is where all the projects I see get hampered.

If something is out of whack, you can backtrace it to: (1) a person or group making a poor decision, or (2) a historically good decision that simply hasn’t aged well, usually outliving the circumstances that prompted a decision in the first place.

We’re ultimately looking at ripple effects born from Conway’s Law:

Any organization that designs a system (defined broadly) will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization’s communication structure.

— Melvin E. Conway, 1967

Our root goal in realigning The Ask will be to eliminate (or at least reign in) the NDA’s influence and tendency for chaotic decision-making by moving the decision-making to the “right” place.

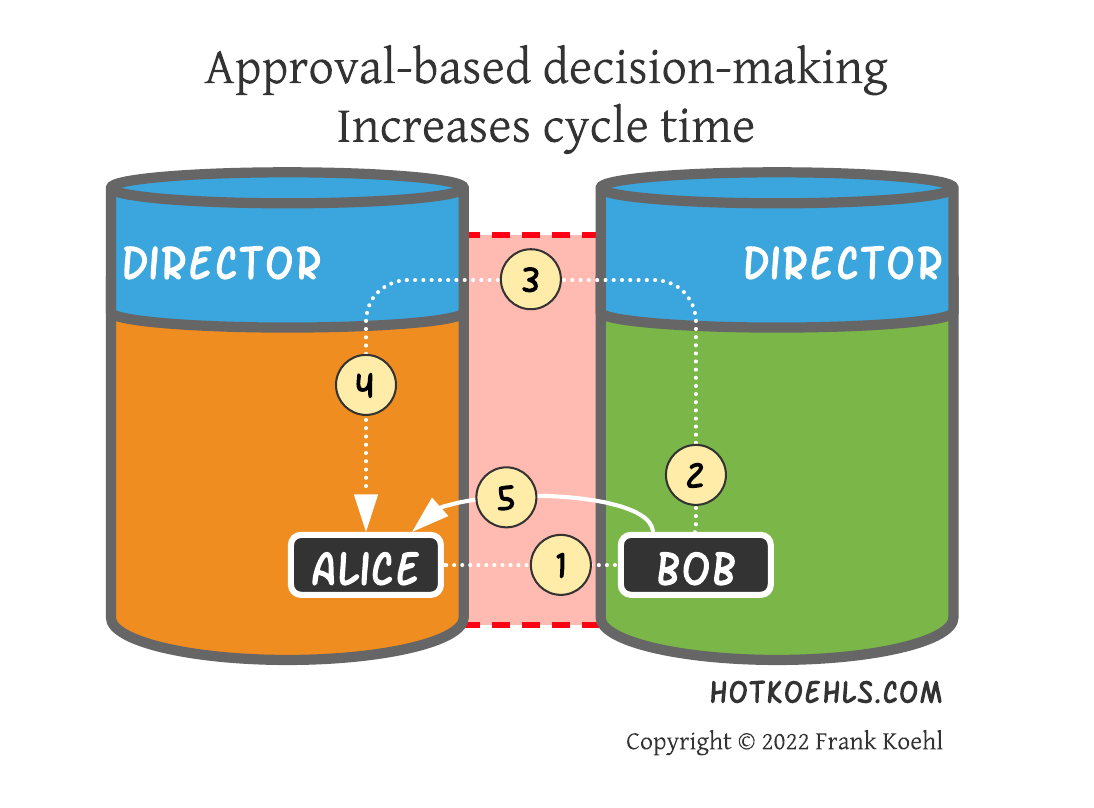

Let’s zoom in on the red area of our first image to illustrate this friction.

You’ve likely seen some form of this inertia-inducing cycle in play before. Details will vary, but the basic setup is something like:

- Alice asks Bob for help

- Bob seeks approval from his supervisor

- Bob’s supervisor confirms work with their counterpart in Alice’s department

- Alice’s supervisor gives her the go-ahead to work with Bob

- Alice and Bob collaborate as approved

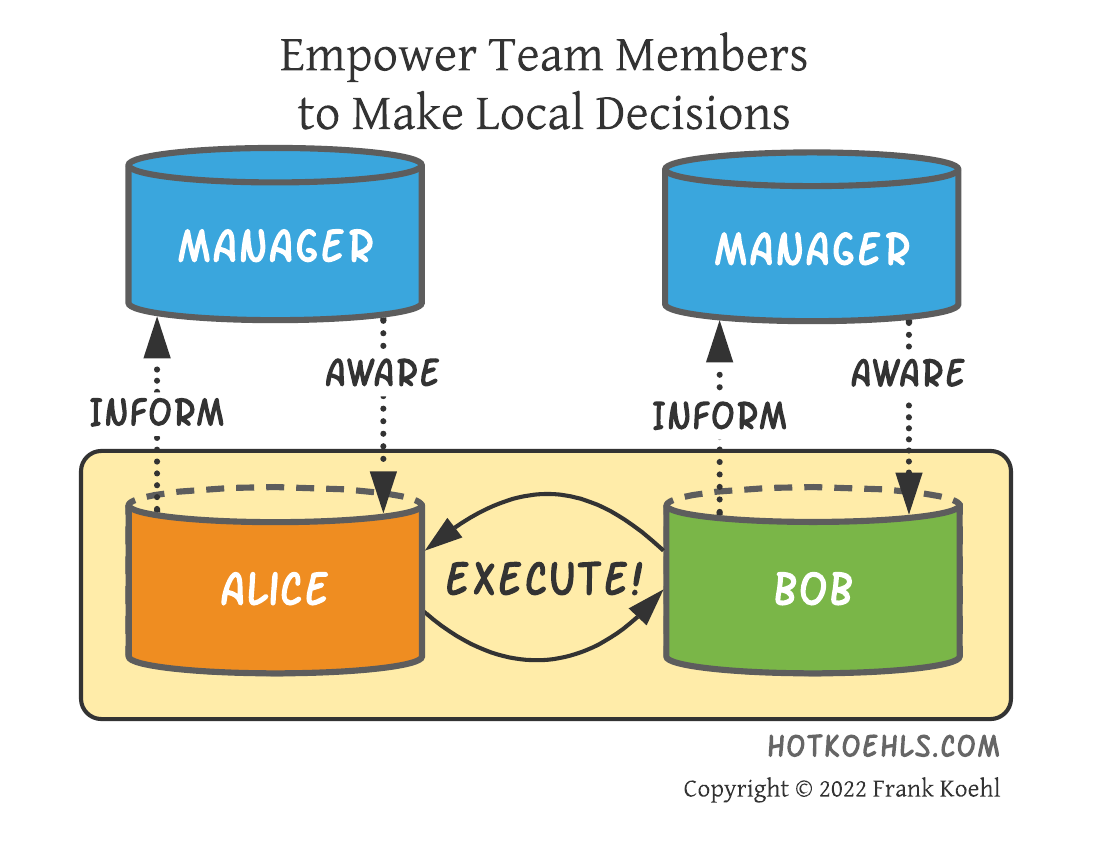

If we assume that Alice and Bob are both Grown-Ass Adults (tm), capable of executing their job responsibilities without constant supervision, then steps 2, 3, and 4 are redundant noise.

The only steps that really matter are:

- Alice asks Bob for help

- Alice and Bob collaborate

as approved

All other people and steps outlined in the “slow cycle” noise is NDA influence, aimed at ensuring “we own the work” and/or “we get the credit.”

One sage colleague of mine puts it like this:

If you can’t trust your people, you should fire them.

If you cringe at the thought of staff in your company having this level of autonomy and self-direction, then you have a hiring problem, and probably a culture problem as well. Discussions for another day.

comments powered by Disqus